Global Wage Report 2022–23

The impact of inflation and COVID-19 on wages and purchasing power

2. The global economic and labour market context

.2.1. Economic growth

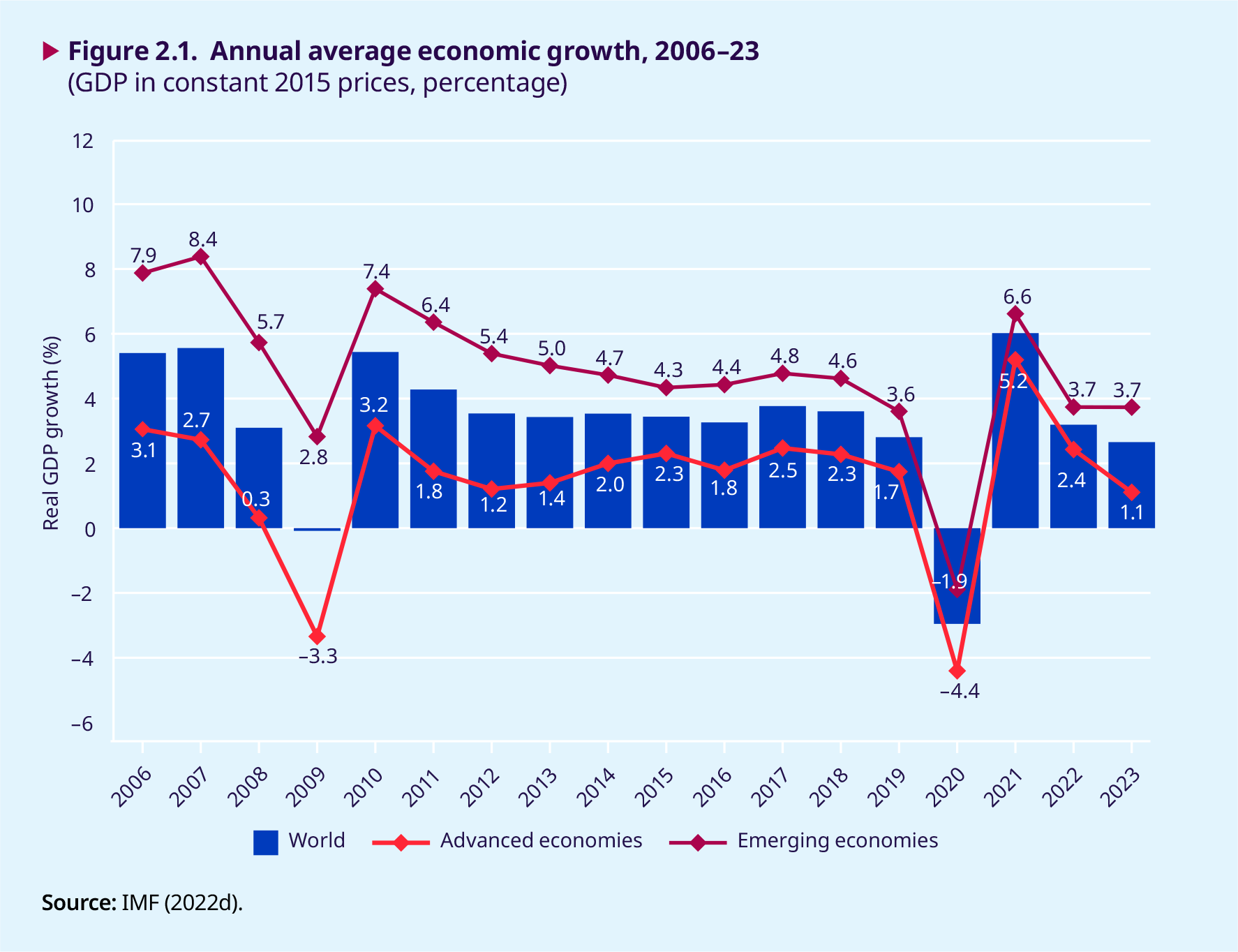

After the collapse of global economic growth in 2020 owing to the measures taken worldwide to control the spread of COVID-19, global output rose strongly during 2021 in both advanced and emer- ging economies (figure 2.1). This was the strong- est post-recession jump in growth in 80 years and may be explained by a rapid rebound in aggre- gate demand as many countries started to grad- ually relax the pandemic-related measures in the course of 2021 (World Bank 2021). Thus, by the end of 2021, global economic growth had increased by 6.1 per cent, with economic growth increasing by 5.2 per cent among advanced economies and by 6.6 per cent among emerging market and develop- ing economies (IMF 2022b).

One critical factor behind this remarkable growth recovery has been the progress in vaccination against COVID-19. By early October 2021, the share of fully vaccinated people worldwide had reached about 35 per cent, and as vaccination rates started to increase in countries where vaccines were swiftly rolled out there followed a gradual relaxation of lockdown measures and a decline in workplace closures. Vaccine access and coverage remain unevenly distributed across the world. According to the latest WHO estimates, more than 74 per cent of people were fully vaccinated in high- and upper-middle-income countries, compared with 57 and 19 per cent in lower-middle- and low- income countries, respectively. Unfortunately, most emerging economies and almost all low-income countries did not have the fiscal capacity to launch the stimulus packages required to mitigate the socio-economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis and kickstart their economic recovery. The IMF estimates that, out of the US$17 trillion spent globally on such packages up to the end of 2021, only about 0.4 per cent can be attributed to developing countries, while advanced and emerging market economies accounted for, respectively, 86 per cent and 14 per cent of the total (IMF 2021). This clearly points to a “fiscal stimulus gap” that is likely to cause advanced and emerging economies to follow diverging paths in the recovery process (ILO 2021a).

The war in Ukraine since February 2022 and other growing crises of a regional nature or with a global dimension (such as the cost-of-living crisis to be discussed further down) have dampened expectations of progress in the post-COVID-19 recovery. Accordingly, IMF projections suggest that the global economy will grow by 3.2 per cent in 2022, down from the 3.6 per cent forecast in April 2022, and by between 2 and 2.7 per cent in 2023 (IMF 2022b). One of the regions that may be worst affected by the war in Ukraine is Europe and Central Asia – in part owing to its geographical location, which implies close trade, financial and migratory ties with Ukraine and the Russian Federation, and in part because most countries in the region depend on the Russian Federation for their energy supplies. Economic growth in the European Union (EU) is thus expected to be no more than 2.6 per cent in 2022 and to decrease to 1.2 per cent in 2023, while in European emerging and developing economies growth is projected to be –1.4 per cent in 2022 and is expected to recover only slightly to 0.9 per cent in 2023 (IMF 2022b).

.2.2. The evolution of public debt

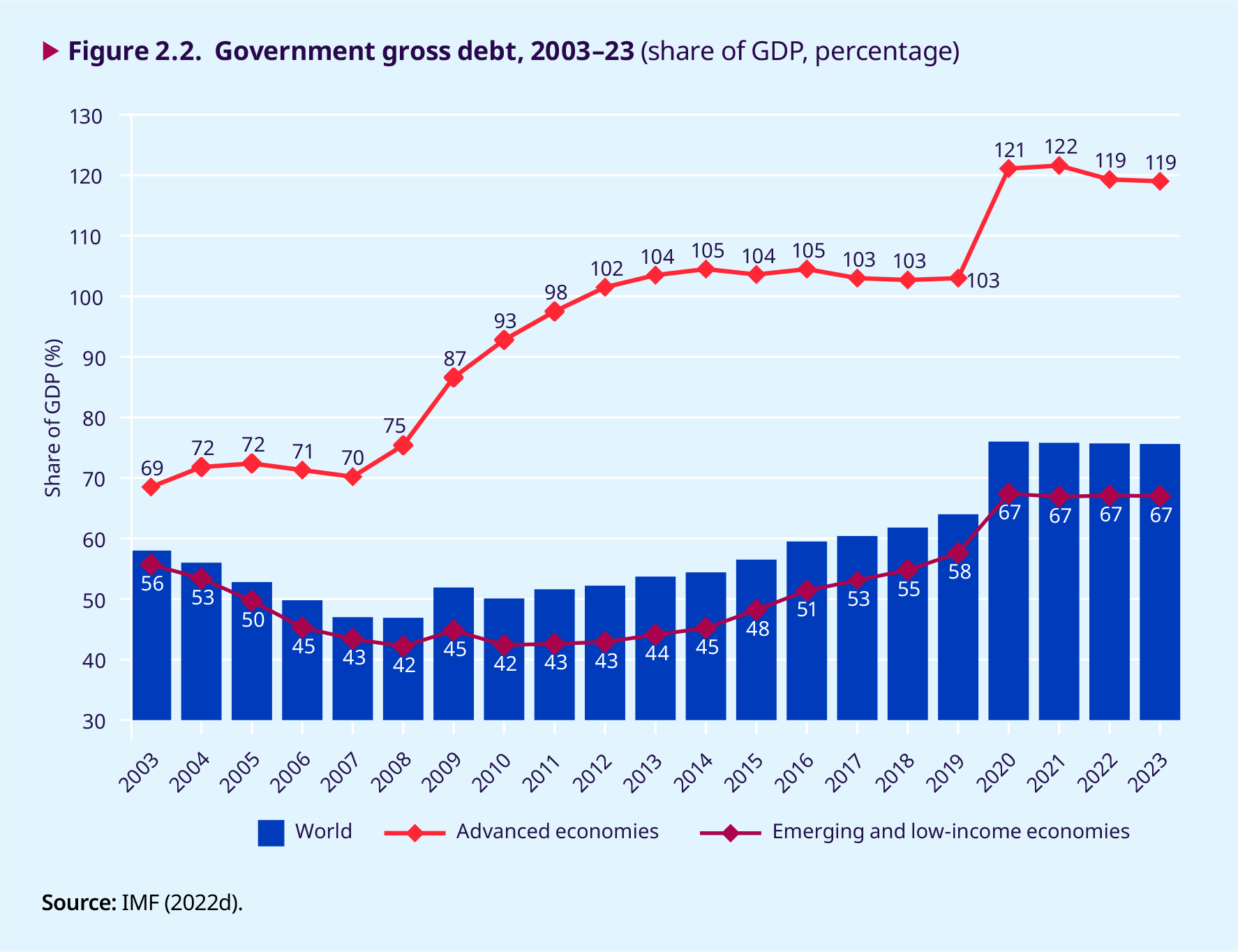

In advanced economies, the unprecedentedly mas- sive public spending during the COVID-19 crisis has led to a significant increase in government debt. Figure 2.2 below shows debt among these coun- tries increasing from 103 per cent of real GDP be- fore the pandemic (2019) to 121 per cent in 2020, a ratio that seems to have stabilized at around 119 per cent after 2021. In contrast, debt in emer- ging market and developing economies increased less steeply, from 57.6 to 67.4 per cent of real GDP over the same period.

Following the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the fis- cal outlook is increasingly uncertain, particularly for countries in Europe. According to the IMF, in a posi- tive geopolitical scenario involving a quick end to the war, debt in advanced economies would fall to about 113 per cent of GDP by 2024. It is worth noting that advanced economies have far more fiscal leeway than emerging market and developing economies, where debt is also expected to decline but there is greater uncertainty owing to a weak recovery, limited fiscal space, and volatile commodity prices.

.2.3. Inflation rates

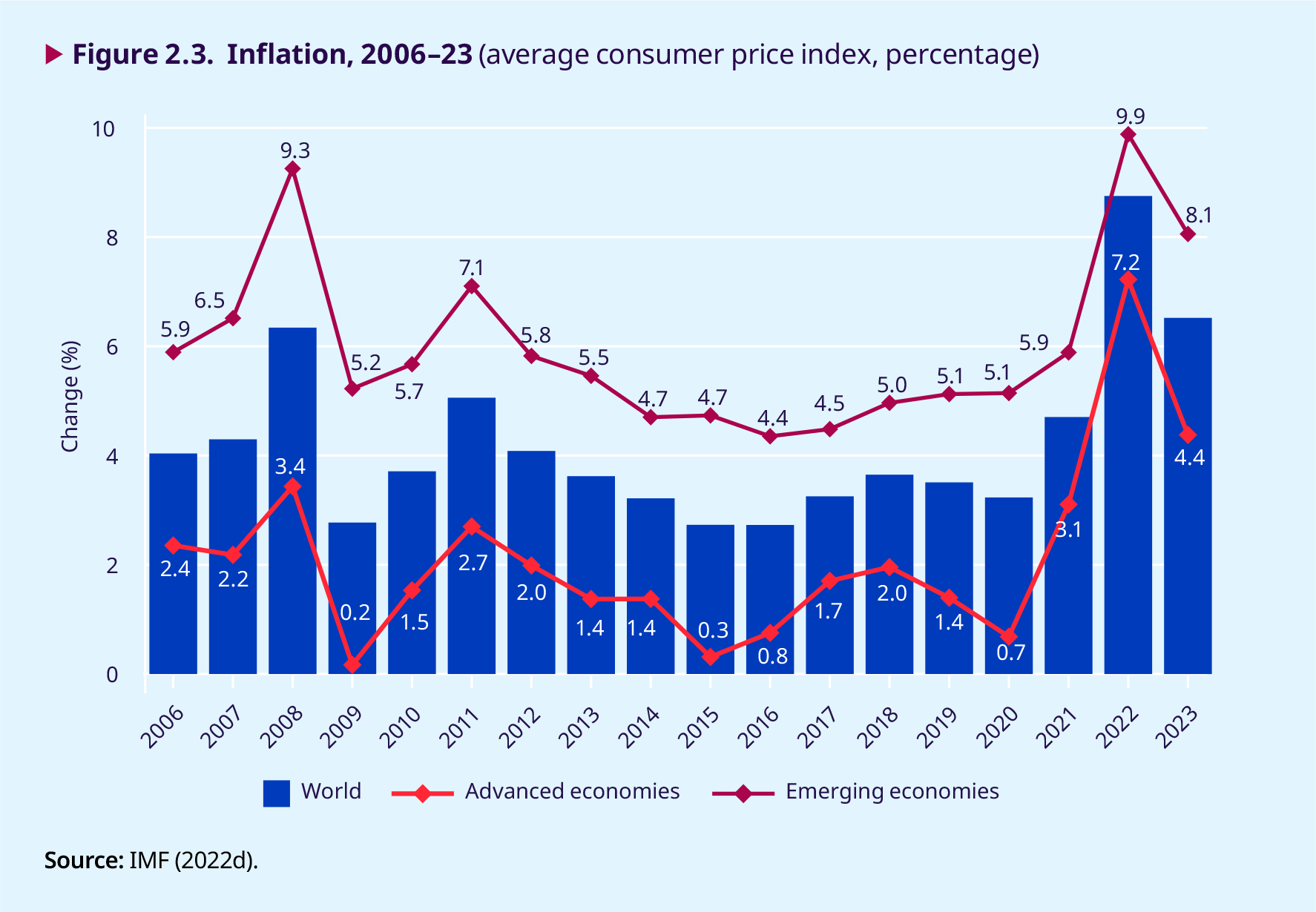

Across all regions of the world, the war in Ukraine has accelerated the increase in prices, which were already rising markedly in the course of 2021, as can be seen in figure 2.3. This has alarming impli- cations for wages, since rising inflation is likely to erode their real value unless nominal wages keep up with price levels. Significantly, the October IMF projections for 2022 shown in the figure are 0.8 per- centage points and 0.9 percentage points higher for advanced and developing economies, respectively, than the projections originally published in April 2022 (IMF 2022c).

Inflation is currently one of the major concerns of policymakers at the national and multilateral levels. A quick glance at the news in most countries shows that more headlines are now devoted to soaring in- flation and its impact on the purchasing power of households than to the effects of the COVID-19 cri- sis. As suggested by the available data, consumer prices had been on the rise throughout 2021 and have continued to increase even faster since the start of 2022. Figure 2.3 shows that inflation among advanced economies rose by 2.4 percentage points year on year over the period 2020–21, whereas over the period 2021–22 it is expected to increase by a further 4.1 percentage points. Among emerging market and developing economies, the increase over the period 2021–22 is expected to be 4.0 per- centage points, with inflation reaching 9.9 per cent by the end of 2022. During 2023, it is expected that inflation will drop considerably in both groups, as shown in figure 2.3.

The recent surge in inflation is often ascribed to the supply bottlenecks resulting from COVID-19-related restrictions, but analysts are also citing additional factors. In particular, it has been suggested that inflation was inevitable because of the stimulus packages adopted to overcome the COVID-19 crisis coupled with the loose monetary policy of central banks over the past few years. The war in Ukraine has compounded the influence of these earlier developments to push inflation even higher. It has also been pointed out that some large corporations may have taken advantage of the inflationary environment to raise their prices and profits (Zahn 2022).

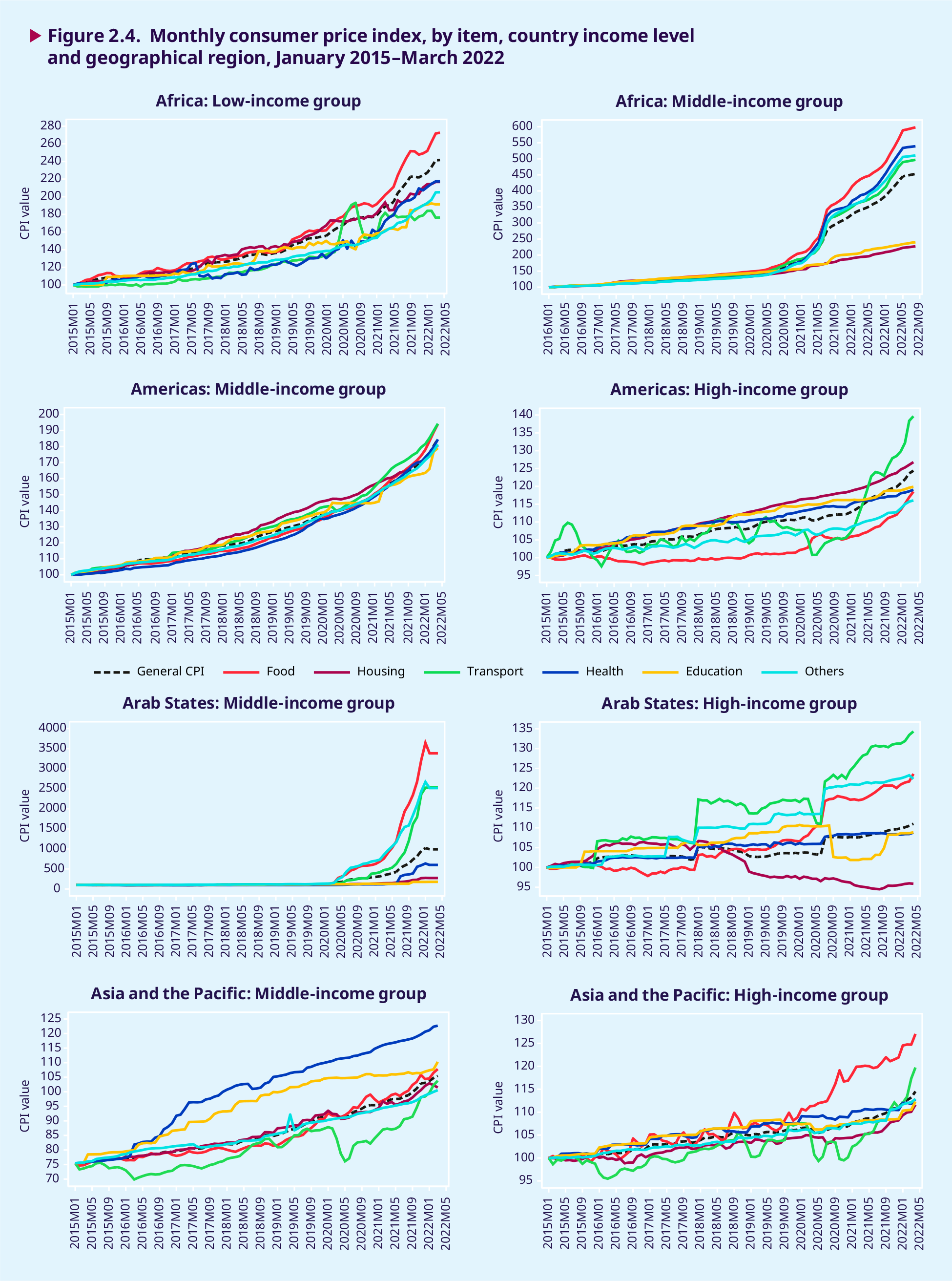

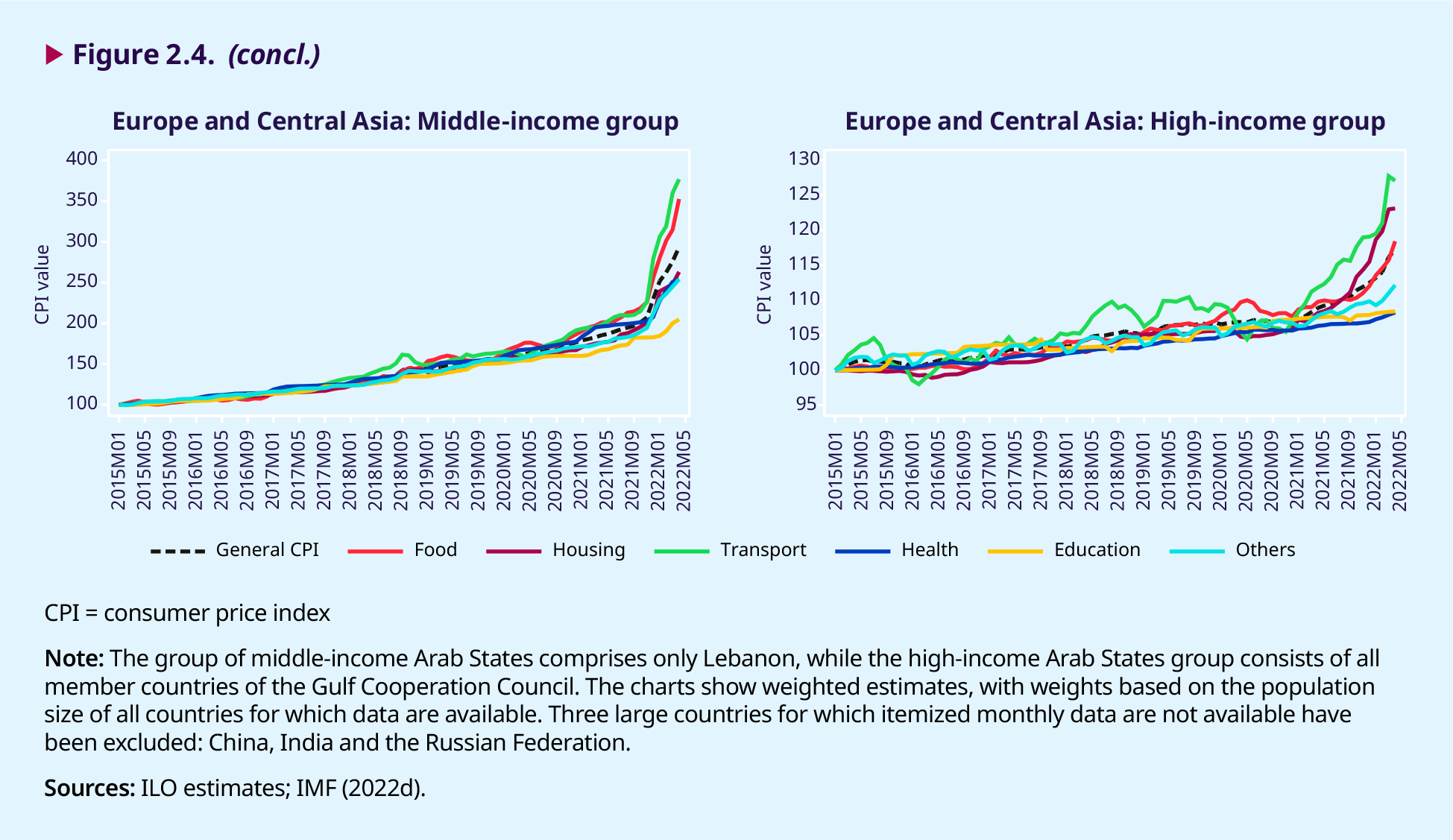

The items in the basket of goods and services that are most likely to experience large price increases are those with an inelastic demand, such as food, housing, transport and energy. For example, annual inflation in the eurozone was expected to reach 8.1 per cent by May 2022, driven largely by a 39 per cent increase in energy and food prices (see Eurostat 2022). Covering the period from January 2015 to March 2022, figure 2.4 shows how the latest inflation trends stand out from those of previous years across regions and income groups, and how the items with the greatest price increases are food, housing, energy and transport. As will be discussed in Chapter 3, these basic goods have a greater weight in the basket of lower-income households than in that of households at the top of the income distribution.

.2.4. The labour market context

The lockdown measures imposed during 2020 and 2021 to contain the spread of the coronavirus plunged labour markets around the world into an unprecedented crisis. From the second quarter of 2020, there was massive destruction of employment and economic activity, which affected both women and men but reduced the global employment of women by 1.2 percentage points more than for men. The crisis also resulted in a significantly smaller share of lower-paid workers in the labour force in 2020 than in 2019, as low-wage earners suffered disproportionately in terms of employment and working-hour losses (ILO 2021a). This contributed to an increase in income inequality (World Bank 2022), possibly reversing the decline in inequality observed in some emerging and low- income countries in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic (ILO 2021b).

At the same time, the crisis has expedited the adoption of novel modalities of work, including telework, that would otherwise have taken much longer to gain traction. While the extent of the use of telework at the global level has yet to be properly assessed, some estimates give an idea of the massive growth of telework in some regions and countries. For example, approximately 34 per cent of all employees in the EU countries started teleworking during 2020 (Ahrendt et al. 2020). In Latin America and the Caribbean, it is estimated that around 23 million workers embraced teleworking during 2020–21, which is approximately 23 per cent of the 98 million wage employees in the region (Maurizio 2021). The full impact of COVID-19 on the use of telework in the future remains to be seen. However, it is likely that teleworking rates will remain significantly higher than they were previously. Post-pandemic telework is expected to follow a hybrid pattern, with people working part of the time in an employer-provided workplace and part of the time remotely.

Another important policy measure adopted to counteract the economic and labour market effects of the crisis was the use of public funds to support the wages of workers in enterprises directly affected by the pandemic so that they could continue in employment. The arrangements for the provision of wage support varied between countries depending on their regulations, institutions (including social protection systems) and, above all, the capacity of their governments to undertake such interventions at short notice (ILO 2020b). Although several emerging and low-income countries adopted such measures, this happened much more frequently among advanced economies. By the end of 2021, as lockdown measures were lifted, employment had returned to pre-crisis levels or even surpassed them in most high-income countries, but employment deficits persisted in some middle-income countries. Moreover, employment recovery has been slower for women than for men, which has led to a widening gender employment gap worldwide (ILO 2022b). Although data for all of 2022 are not yet available, estimates for the first quarter suggest that global working hours remain about 3.8 per cent below the level of the last quarter of 2019. Across country income groups, low-income countries are lagging behind in the first quarter of 2022, with 5.7 per cent fewer hours worked compared with the last quarter of 2019, while high-income countries have recovered the most, with 2.1 per cent fewer hours worked in the first quarter of 2022 compared with the last quarter of 2019 (ILO 2022b). The recovery of working hours has been slower for women than for men in low- and middle-income countries, in contrast to high-income countries, where the number of hours worked by women has recovered faster (ILO 2022c). Overall, the gender gap in hours worked has been widening globally.

Estimates also show that certain groups in the labour market suffered more severely than others, particularly during the period leading up to the end of 2020. These include low-wage workers, workers in the informal economy, wage workers in temporary employment, women and young workers (ILO 2021b). Wage employees in the infor- mal economy were hit particularly hard. Informal wage employment dropped by 12.3 per cent glo- bally in the fourth quarter of 2020 relative to the same quarter in 2019, while formal wage employ- ment decreased by just 1.6 per cent over the same period (ILO 2022c). After the big losses in the sec- ond quarter of 2020, informal employment began to increase faster than formal employment, and by the last quarter of 2021, the recovery in informal employment had overtaken that of formal employ- ment. Three factors were behind this development: (a) the return of many informal workers to their economic activities; (b) the taking up of informal employment by people who were previously out- side the labour force to compensate for losses in household income; and (c) the informalization of previously formal jobs. This third trend has yet to be confirmed empirically, but such informalization already seems to be significant in some sectors, in- cluding construction and wholesale and retail trade (ILO, forthcoming).

Workers in temporary employment were strong- ly impacted by the crisis. For example, in Mexico, Poland and Portugal, 33 per cent, 9 per cent and 17 per cent, respectively, of those who were in temporary employment in the first quarter of 2020 were out of work in the second quarter of 2020, compared with just 12 per cent of non-temporary workers in Mexico and 3 per cent in both Poland and Portugal (ILO 2022c). Young workers seem also to have been worse affected by the crisis. While young people made up just 13 per cent of total employ- ment in 2019, they accounted for 34.2 per cent of the decline in employment in 2020. The change in the employment-to-population ratio between the second quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2021 suggests that, despite some improvements, young people, especially young women, still faced the biggest deficit relative to the pre-crisis situation in 2019 (ILO 2021a).

The further recovery of global, regional and national labour markets depends very much on the socio- economic impact of the ongoing crises – particularly the cost-of-living crisis, but also geopolitical turmoil, driven mainly by the war in Ukraine. Current geopolitical tensions, together with the rising cost of living, could in fact cause the recovery in employment levels to deviate from the trajectory that had been projected for the end of 2022. This will certainly be the case if the war in Ukraine does not end before long. In such circumstances, the war’s impact on energy prices and further bottlenecks in the supply of goods needed for production will continue to slow down global growth during 2022. With only a few exceptions (such as oil- and gas-exporting countries), employment and economic output in most countries are likely to remain below pre-pandemic levels till the end of 2026 (IMF 2022c).